In Pathways To Ponty, I made a big play of the parallels between Jean-Luc Ponty’s “The Gardens Of Babylon” and Stacey Pullen’s “Vertigo”, but it's the other comparison I made — tucked away in a footnote at the end of the piece — to Massive Attack’s Protection that I keep coming back to. There's always been an intrinsic symmetry to that album — the way its second side perfectly mirrors the first — its carousel turning through torch songs with Tracey Thorn, menacing posse cuts from back when Tricky was still in the fold, Nicolette’s trademark otherworldly chansons, moody instrumentals, and dubbed-out roots music with Horace Andy in the driver seat. The whole experience squares trip hop's pre-millennium tension with the half-lit spirit of soundsystem soul,[1] spiked with more than a touch of the sort of late night jazz that used to creep onto the airwaves as twilight fell and boundaries loosened with the passing moonlit hours.

This hits you strongest in the album's twin instrumentals, “Weather Storm” and “Heat Miser”, both of which feature solo piano from Craig Armstrong, who also arranged the orchestration for “Sly” (featuring vocals from the inimitable Nicolette). “Weather Storm” is one of those tunes that truly embodies the essence of its title, as Armstrong’s piano meanders across a lush, overcast soundscape driven by a throbbing, overdriven bassline and gently ticking beats, you can practically hear the falling rain and distant, rolling thunder through the spaces between. Armstrong actually revisited “Weather Storm” on his debut LP The Space Between Us — produced in the wake of his star-making turn scoring Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet — a few years later, stretching out out the tune and deconstructing it into the quintessential “invisible soundtrack.”[2]

It's at the axis of Armstrong’s interlocking maze of piano and orchestration that I'm reminded of “The Gardens Of Babylon”, the second track from Jean-Luc Ponty’s Imaginary Voyage LP. I find there's a real similarity to Armstrong’s work in the interplay between Ponty’s electric violin and Allan Zavod’s Fender Rhodes, where both instruments seem to melt into each other like butter in the afternoon sun. When Zavod (who debuted in Ponty’s band with this album, picking up the baton from Patrice Rushen) comes in for his piano solo one-and-a-half minutes into the song, it all but seals the deal. I don't know whether it was 3D, Mushroom Vowles, Daddy G, or even Craig Armstrong, but I'd swear that someone in the Massive camp must have been hip to this record. Truth be told, it wouldn't be much of a stretch...

After all, Massive Attack had been no stranger to the sounds of jazz funk and rare groove, going all the way back to their debut album Blue Lines. They sampled low-slung fusion tracks like Billy Cobham’s “Stratus” and Mahavishnu Orchestra’s “You Know, You Know”[3] from genre touchstones Spectrum and The Inner Mounting Flame (respectively), the smoothest soul in the shape of Lowrell’s “Mellow Mellow Right On” and Isaac Hayes’ “Ike's Mood I” (even going so far as to cover William DeVaughn’s deep soul chestnut “Be Thankful For What You Got”), and requisite jazz funk like The Blackbyrds’ “Rock Creek Park” (in the spirit of the times). There's a strong current of this sort of deep jazz flavor running through songs like “Safe From Harm” and the title track, anchoring the album in a certain rare groove sensibility even as it draws equally from the twin wells of The Bronx and Jamaica.

This relative comfort with jazz forms really paid dividends on Protection, the group's follow-up album, where it blended with the rootsical dub and overcast hip hop sensibilities of Blue Lines in a swirling cocktail of liminal Bristol blues. There's a real windswept drift to Protection — particularly the three songs featuring the input of Craig Armstrong — that I've often thought has a strong affinity with the lush climes of post-fusion jazz. It's as if every corner of the soundscape were shrouded in shadows and velvet, even as the production remains remarkably crisp and tactile throughout. There's certainly parallels to be found in the ethereal, Gaussian blur of Ponty’s Imaginary Voyage, particularly tracks like “Imaginary Voyage (Part 4)” and “The Gardens Of Babylon”, the latter seeming to exist somewhere in the nexus between Craig Armstrong’s three contributions to Protection: “Weather Storm”, “Sly”, and “Heat Miser”.

It's as good a thumbnail sketch as any for the nocturnal, jazz-inflected terrain I was hinting at earlier. I have all sorts of fond memories of this music — and the social situations that seemed to emerge around it — from back in the day. This music was often casually inventive, open to the possibilities of the cosmos (likely a hangover from the era of Impulse!, Sun Ra, and astral jazz), with even the occasional new age inflection folded into the whole affair for added dimension. Driven by almost subliminal head-nodding grooves and a general mood that was supremely chilled to the bone, its sound would often overlap with the sort of downbeat abstraction one might have found on labels like Compost and G-Stone, even if your friends might have given you a hard time and say “it all sounds like elevator music.” There's any number of great examples I could cite here, from Sun Palace’s Winning to Dave Stewart & Candy Dulfer’s Lily Was Here, but one that strikes me as rather apt in today's company is Pat Metheny’s 1995 album We Live Here.

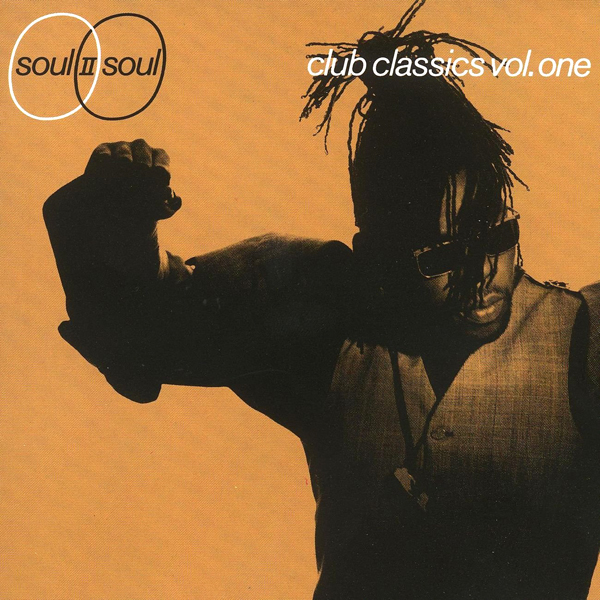

There's plenty of contemporary flourishes to be found here, from the acid jazz of “The Girls Next Door” to fusion-as-drum 'n bass experiments like “Stranger In Town” and the title track, but most salient to our purposes tonight is “To The End Of The World”. A twelve-minute understated tour de force of downbeat, smooth jazz funk, it moves in and out of focus through atmospheric passages (shades of The Orb) and fragile piano solos where the band sounds like it's moved off to play somewhere in the distance, ultimately rising to fabulous crescendos of iridescent guitar over Soul II Soul-style beats and a driving wood bass groove before collapsing back again into pure atmosphere with the distant rumble of thunder. It's emblematic of a time when boundaries were being blurred between jazz, hip hop, and dance music almost as a matter of course, an era when a genre like garage could flourish just below the mainstream threshold, hovering somewhere between the twin poles of modern soul and post-disco house.

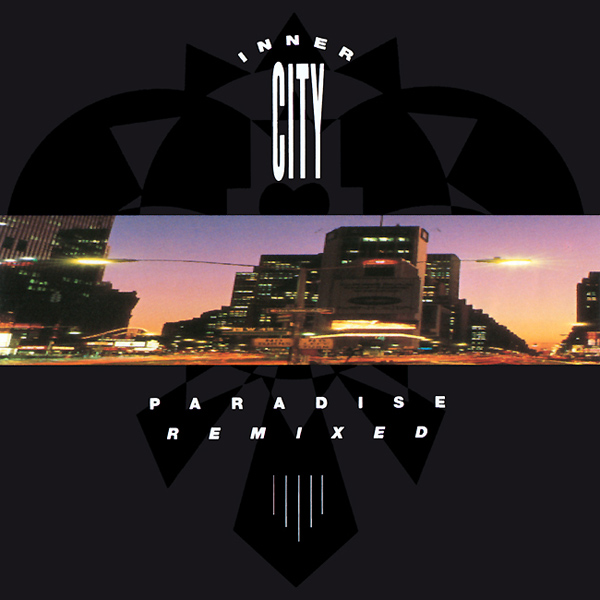

If you're looking for an example of that, you'd have a hard time finding a better one than this record. The lush eight-and-a-half minute epic “Watcha Gonna Do With My Lovin' (Knuckles/Morales Def Mix)” is a perfect illustration of the interface between underground dancefloors and the pop landscape of its day. Inner City was Kevin Saunderson’s pop-oriented project featuring the vocals of Paris Grey, a project that took on a life of its own when their song “Big Fun” became a surprise hit in 1988 on the back of the Techno! The New Dance Sound Of Detroit compilation, leading to the group playing Wembley Stadium alongside Salt-N-Pepa even as Saunderson was still putting out weird underground records like Reese’s Rock To The Beat and Just Want Another Chance (quintessential Detroit techno by any metric).

This 12" — a cover version of the old Stephanie Mills disco classic[4] — came on the heels of the duo's debut album Paradise, bringing in Frankie Knuckles and David Morales to give it their trademark silky-smooth def touch (the full eight-and-a-half minute mix also cropped up on Inner City’s Paradise Remixed compilation, rendered essential by this fact alone). From tonight's standpoint, this is where things get interesting, because I've always thought that this midtempo garage burner just so happened to parallel contemporary developments happening over in Bristol at the time, particularly things like Soul II Soul’s Club Classics Vol. One, a lot of Smith & Mighty’s early productions, and (slightly later) Massive Attack’s “Unfinished Sympathy”.

More to the point, it's also the third part of tonight's discussion, rounding out the trilogy with Massive Attack’s “Weather Storm” and Jean-Luc Ponty’s “The Gardens Of Babylon”. Check out the way those pianos roll out across the soundscape like a gently flowing stream of water, the beat like a long, winding trail of smooth stones rising from the bedrock and coming into play to change the river's course before phasing out completely, the one constant that recurring interplay of gospel-drenched strings and piano (as with the other tracks here, melting together as one in liquid ambience). Even when those strings take on a certain stridency — interestingly enough, seeming to quote Marshall Jefferson’s “Move Your Body” — it's just a momentary storm in the greater placid calm of the tune in question.

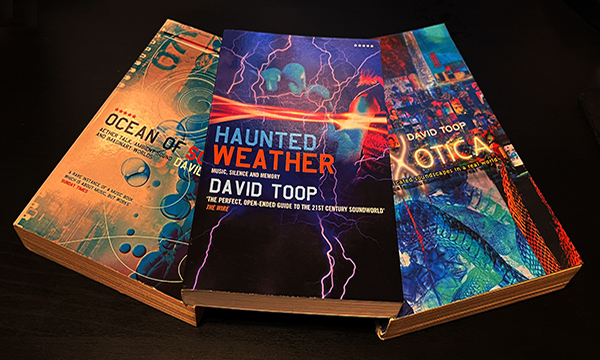

That sense of zen-state ambience in the midst of heavy weather — the calm within the storm — ties this loose trilogy of songs together beyond even their melodic similarities or parallels in production, bringing a certain thematic continuity into focus between the grooves of these records. Each of them drift comfortably into the territory laid out by another trilogy, David Toop’s Ocean Of Sound (Ocean Of Sound, Exotica, and Haunted Weather), which chronicles music's ability to draw the listener in, immersing you in the atmosphere of its own sonic world. Sound waves rise and fall from the grooves of these records, washing over you like the tide sweeping in across the shoreline, enveloping you in a weather storm of the mind.

Footnotes |

|

|---|---|

|

The bottom-heavy post-hip hop soul sound of late-eighties U.K. that both paralleled the development of trip hop and prefigured the American r&b explosion of the following decade. |

|

|

The effect is not unlike Nightmares On Wax’s serial re-imaginings of “Nights Interlude”, where the original song was drawn out into ever more sweeping arrangements and epic scope in later versions like “Night's Introlude” and “Les Nuits”. Still, if I'm being brutally honest, in both cases nothing touches the elegant simplicity of the both song's original versions. |

|

|

“You Know, You Know” also features none other than Billy Cobham on drums, before he struck out on his own with Spectrum (the album with “Stratus”) in 1973. Interestingly enough, Stacey Pullen sampled Cobham’s killer breakbeat from Mahavishnu’s “Vital Transformation” for the track “Futuristikfreakqueen”, a wild-eyed stab at Reprazent-style bionic jazz-meets-drum 'n bass from Todayisthetomorrowyouwerepromisedyesterday. |

|

|

Penned by none other than household hero James Mtume and partner-in-crime Reggie Lucas. |

|