Slim Slow Slider,

This whole thing started out innocently enough, tucked away as a little contextual footnote at the end of another piece of writing I've been putting together for you over the past couple months. Of course, it all got out of hand relatively quickly, and since the last thing anyone needs is footnotes within footnotes, I wound up taking a step back to rethink my whole approach. Since this particular fragment is really a whole other story in its own right, I decided to roll it out properly on its own and bump it to the front of the queue, so as to to kick off this ongoing dispatch that I plan to bless and burden you with in the coming weeks, months, and years.

We'll see if I can keep it going...

The reasons for this are threefold: one, these are all (mostly musical) subjects that would likely interest you. I hope they come as a welcome diversion — a mental vacation of sorts — as you go about your week, moving through the world and taking care of business. Two, I'd love to hear your reactions and insights on this stuff, because your takes are always very interesting to me. Over the years, we worked our way through the world of music at different — if often intersecting — angles, so I'm curious what you think about this or that record, how you imagine such and such a figure fits in with the other surrounding puzzle pieces, or even if there's anything else it might remind you of (as you know, I'm always on the lookout for a hot tip!). And three, it's a chance to mess around with writing again, since I haven't had a chance to put down any real ideas for about a year and a half now (yikes!).

To that end, I've been cooking up a couple special batches for you since January, writing about some beats that have been on my mind and on the tables for weeks at a time. This was simply the first one to make it out of the broiler, a tasty little morsel sliced off a more substantial hunk of hip hop homage that will most likely make its way to you in the weeks to come. As this particular little tangent began to take shape, I quickly realized that it's as good a place as any to start getting to the heart of everything I love about music, to tease out the common threads running through it all and tie them back together in a crackling network of sound. At the end of the day, I suppose it's really just an attempt to capture “the flavor that they savor up here, neighbor.”

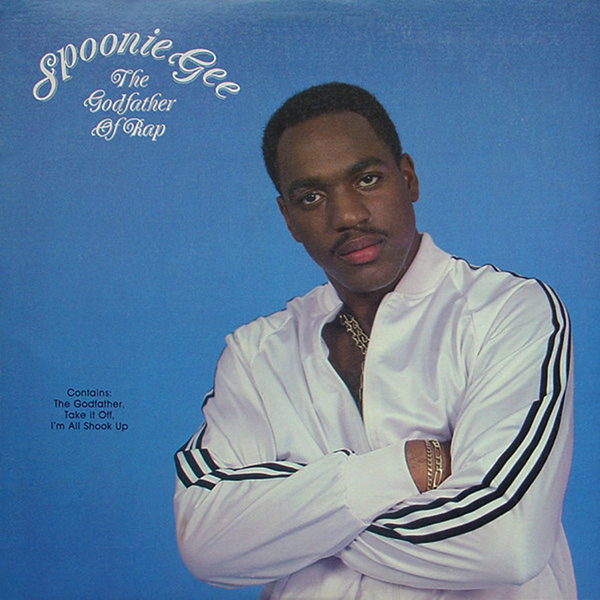

So set your mind back to the year 1998, when the first rap records were already getting to be about twenty years old (even as the latest crop of them ruled the charts with an iron fist) and the spectre of the 1980s began to rise from the ashes of the post-grunge musical wasteland, setting the stage for the early 21st century musical landscape — this after a decade of breakbeat science wound up rerouting it all back to the source, in hip hop's block rockin' beats — because today's jumping off point is the OG MC himself: Harlem’s own Spoonie Gee.

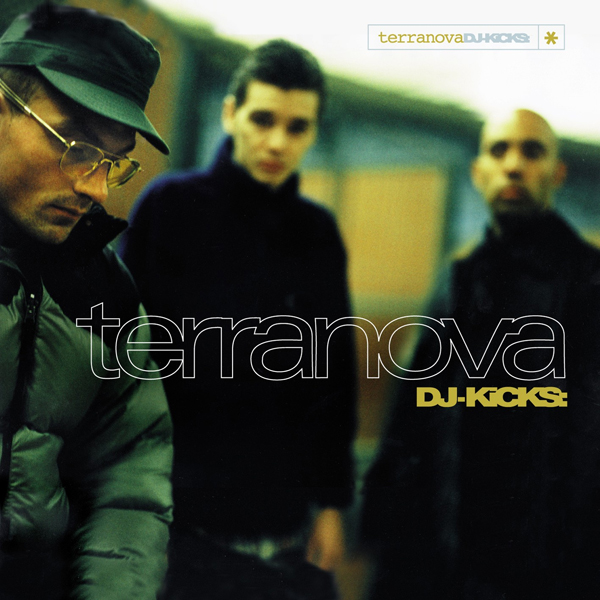

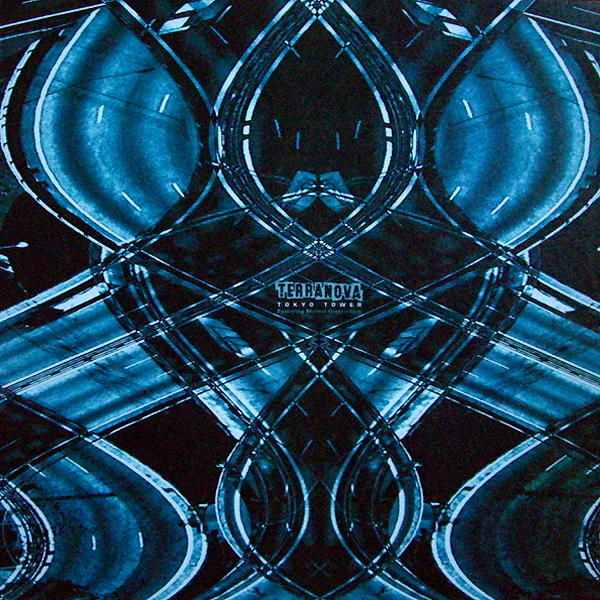

I first heard Spoonie Gee’s “Spoonie Rap” back in high school. Coming in at the tail end of Terranova’s phenomenal DJ-Kicks set,[1] it felt like being dropped through a trapdoor into some basement party down in The Bronx circa 1982, crowd noise hanging in the air while mad unhinged oscillators twist and cascade across a low-slung skeletal funk rhythm bumping and sliding across the dancefloor. The DJ up there somewhere in the background, scratching records down to the bone, coming at you so rough, rugged, and raw that he threatens to drown out Spoonie’s stream-of-conscious wordplay — dancing like a loon out there in front of it all — his freestyle rhymes fed through the Echoplex and occasionally getting sucked into the void altogether.

In the heat of the late-nineties, it was the sort of tune that grew on you slowly, its lackadaisical freeform basement discotheque visions running in stark contrast to both the post-Wu-Tang dread of the rap underground and the flashy widescreen glamour of the shiny suit era. But grow on me it did, feeding into the slowly shifting musical tastes of a typical nineties teenager, then in the process of being forever warped by an inevitable and irreversible descent into the seemingly boundless underworld of post-disco dance music (taking in the sounds of techno, house, rap, jungle, trip hop, electro and all other manner of permutation therein).

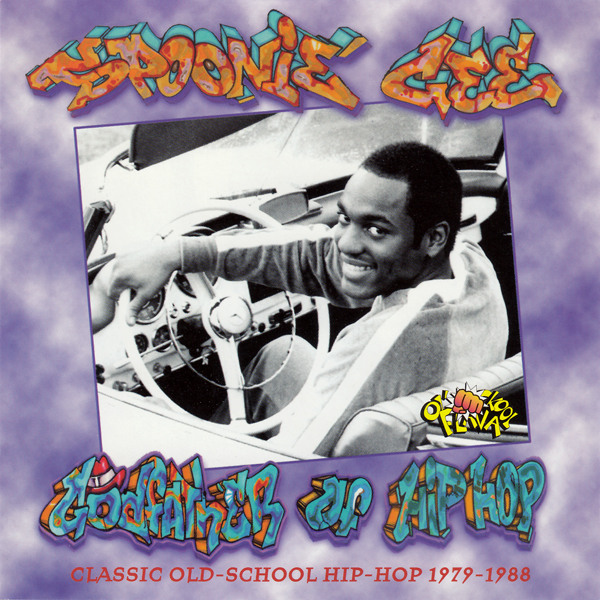

Spurred on by this taste of hip hop's oldest school of all, I tracked down the indispensable Godfather Of Hip Hop compilation, which must have been one of the first rap discs I ever owned (“hey great, no parental advisory sticker!”).[2] Three surprises hit me right off the bat: first, it turned out the tune was actually titled “Spoonin' Rap”.[3] At least that's what I gathered checking out the tracklist in Tower Records, debating whether or not to take the plunge and part with my hard-earned (a gamble that wound up paying off).

Second, after cracking open the CD back at home, I found out that the song dated from what — at the time — seemed like the impossibly early year of 1979. Since I'd always assumed it was from 1983 or thereabouts, that fact alone blew my mind! In those days, my (mis)understanding of early rap history compressed the foundational steps of the 1970s into the first couple years of the '80s, so that “Rapper's Delight” might have emerged in 1981, while “The Message” would have hit in 1984, and something like Whodini’s “Freaks Come Out At Night” might have come a couple years later in '86 or even early '87.[4] Looking back now, a couple years difference might seem like no big deal, but in those days things were still moving so fast that it may as well have been an eternity.

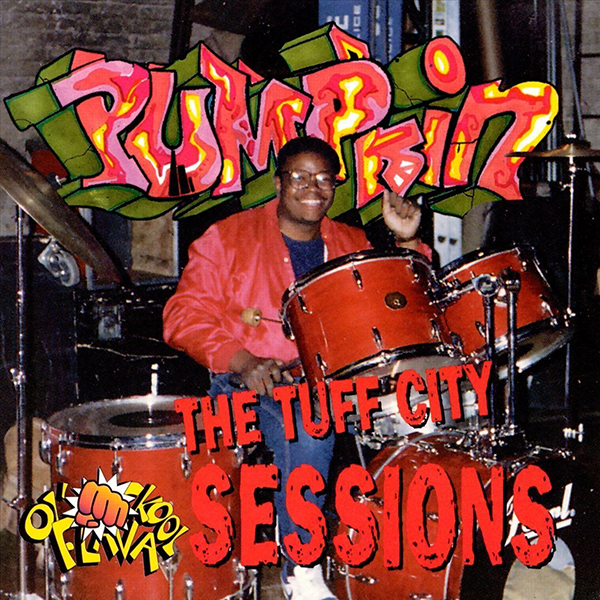

The third and final surprise was the sound of the track itself, since it turned out that the original version of “Spoonin' Rap” was largely free of all the atmospherics I'd grown accustomed to in the mix, stripping it all back down to the core drum and bass rhythm. Laid down by the great drummer/multi-instrumentalist Pumpkin, one of the prime architects of the early live-band hip hop sound,[5] it was a moody backbeat not a million miles removed from the sort of thing Q-Tip might have sampled for the instrumental bedrock of A Tribe Called Quest production circa Midnight Marauders.

The only real remaining adornment to the nimble drum and bass interplay was the flimsy-floaty sound of the Flexatone, an oddball instrument that gave you a whole lot of interstellar bang for your buck (much like the Theremin), cropping up not only in seventies funk and dub records but even some avant garde classical pieces earlier in the 20th century.[6] Just one of many textures on the version I'd been familiar with, here it practically took center stage, moving like some shimmering trickster loa bobbing and weaving in the back of the mix (bringing to mind the lingering spectre of Death in Black Orpheus), flashing strange dub-disco shapes across the downbeat half-light while Spoonie unfurled his convoluted couplets out into the lonely night.

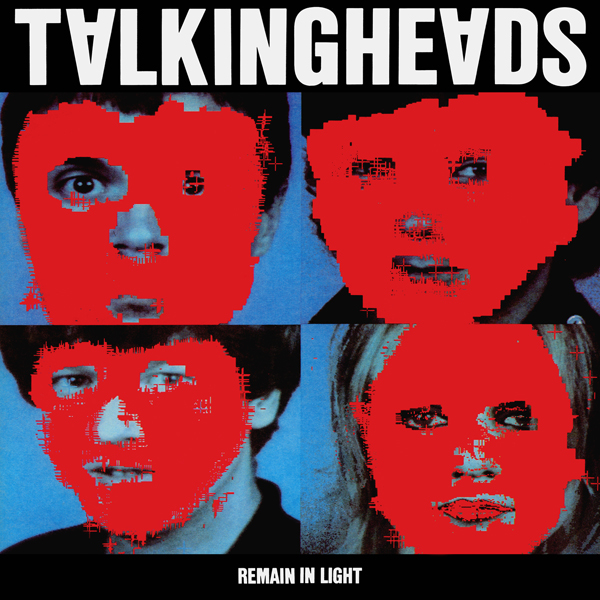

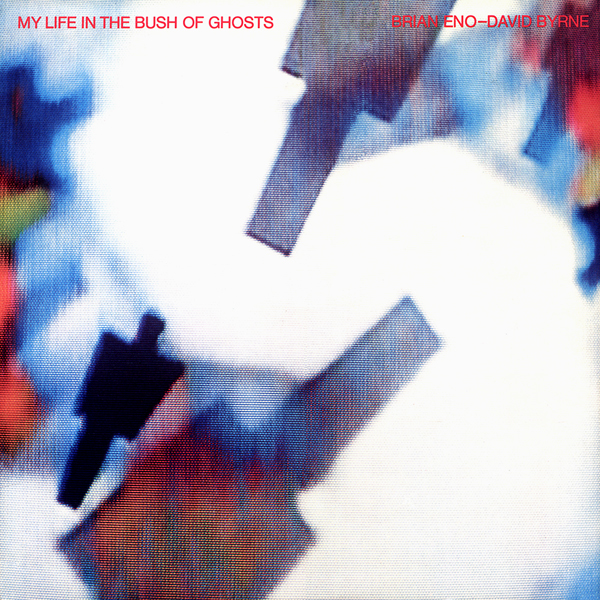

In contrast to the majority of early rap records, which sought to capture the frenetic interplay of a tight-knit crew busting their trademark routines live in the club and transcribe it all straight to wax, this was very much a burnished late-seventies basement studio confection along the lines of Ian Dury & The Blockheads’ Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick or Prince’s For You.[7] I'd even go one step further and place it squarely in the Terminal Vibration continuum, sounding like something that could've slipped off side 2 of Remain In Light (or even My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts) to take a pimp-stroll down Harlem River Drive for the evening, only to cross paths with an errant MC who began unfurling his life story over the top without missing a beat.[8]

Only 17 years old when “Spoonin' Rap” was released,[9] Spoonie Gee was considerably younger than much of rap's first wave vanguard. Rather than cutting his teeth on stage in the clubs, he'd honed his skills out there on his own, freestyling day and night around the house and out in his neighborhood up in Harlem. It was simply one of the many rhymes he'd worked out by the time he set foot in Peter Brown’s studio to put the sounds swirling around his mind down on tape.[10] Much like nineties downbeat excursions on the order of DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing, Earthling’s Radar, and DJ Wally's Genetic Flaw, this was a bedroom dreamer's shoestring ruminations on what was happening out in the streets and down in the clubs, warped ever so slightly by a skewed vision and outsider status, mutating the prevailing sounds of the day in a whole other direction.

From that angle, it makes perfect sense that “Spoonie Rap” would dovetail so naturally with the stuff I was already listening to in the '90s (to bring it all back to me, me, me!).[11] It's not much of a stretch to hear something like Reprazent’s New Forms descending directly from the blueprints laid down by a record like Spoonin' Rap nearly twenty years earlier (it certainly made perfect sense listening to both records back to back at the time). It was also a snug enough fit for just the sort of dashing, good-natured young chap that might have kept the faith with new wave and electropop right through the grungy '90s, snapping up anything with its lingering lipstick traces that he could get his hands on,[12] before the post punk/'80s revival came along to reshape the early 21st century zeitgeist in its image altogether.

By that point, I was already working part-time and had long since taken the plunge into the wonderful world of vinyl,[13] ultimately tracking down the original Spoonin' Rap (12" Single) that came out on Peter Brown’s Sound Of New York, USA imprint. On the 12", both sides have their own version of the tune, each featuring its own unique freestyle weaving its way across the top of what is essentially the same rhythm track. The version I'd known was actually the b-side, subtitled “I Don't Drink Smoke Or Gamble Neither I'm The Cold Crushing Lover” (shades of “Goody Two Shoes”), and it's still my favorite of the two, dropping right into the beat with little fanfare beyond the twang of Pumpkin’s bass and Spoonie’s “na-na-na-yada-yada-yada-na” old school flow.

In contrast, the a-side's “A Drive Down The Street I Was Spanking And Freaking” kicks off with Spoonie tweaking Carl Perkins into the classic rap catchphrase “You say one for the treble, two for the time, come on y'all let's rock” before dropping into a proto-LL Cool J loverman rap that slowly mutates into a naked city travelogue a la Schoolly D’s “Saturday Night”[14] and ultimately devolves into petty crime and scenes from the jailhouse (JUST like in “The Message”). As you might expect, all sorts of key rap catchphrases make their early appearances here, including hip hop evergreens like “yes yes y'all, to the beat y'all,” “la-di-da-di,” “one time for the mind,” and “on and on and on and on like hot butter on — say what — the popcorn.”

By this point, I'd had a chance to hear a lot more music in the interim and came to realize what a truly special track this was (aka the “Whip In My Valise” effect).[15] Far beyond the level of a great tune that I just so happened to love, there was no denying that this was a landmark record, standing outside the timeline as a singular work of pop art. Like Rammellzee vs. K-Rob’s “Beat Bop”, it manages to capture the feeling of a great park joint from ten-to-twenty years later,[16] and only sounds better with every passing year. It was right around this point in time (2004-2006) that it became locked firmly into place within any discussion of my favorite 300 or so records ever.

One thing still bothered me though: I would've loved to get my hands on the full tricked-out version of the track as heard on Terranova’s DJ-Kicks. I'd come to assume that all the extra bells and whistles were Terranova’s own intervention — since they'd already added all sorts of similar goodies of their own throughout the mix[17][18] — and that maybe they'd just slapped the tag “Atmospheric Version” to denote its distance from the original. And yet it wasn't included on the unmixed double-LP version of Terranova’s DJ-Kicks outing, which even included exclusives like the awesome Avenue A remix of “Tokyo Tower”.[19] So what was the deal with this “Atmospheric Version” anyway?

The answer eventually made its way to me with the growth of the internet and Discogs’ seemingly overnight transition from the-little-electronic-music-site-that-could to a full-scale database of recorded music in toto (complete with marketplace!). Right around the time I moved onto Mohawk, I stumbled upon this particular reissue/reworking of apparently dubious vintage.[20] There it all was: the title “Spoonie Rap”, complete with the original 1979 version, a remix (more on this later), and finally the mythical “Atmospheric Version” tucked away on side 2. It even matched the label information provided in the CD's liner notes: Harlem Place.

Percival, it seemed, had found his grail...

It turns out that Harlem Place was one of those blink-and-you-miss-them labels that specialized in reissues of disco-era cuts, usually bolstered by new remixes aimed squarely at mid-nineties dancefloors, and often informed by house and hip hop sensibilities.[21] They put out a string of records in quick succession — also releasing a 12" of Cloud One’s “Atmosphere Strut” — before closing up shop. Beyond that, information remains thin on the ground, although seeing as most of the music happened to spring from Sound Of New York, USA and other Peter Brown-helmed labels like Heavenly Star[22] and TSOB, my first guess is that he would've been involved somehow.

It also makes sense that this record would've been swirling around the shops and record pools at the time Terranova were on the rise and barreling toward their brush with immortality (here on Mohawk, at least), cooking up early records like Antimatter, Tokyo Tower, and The Psychogeography EP before clocking in their DJ-Kicks outing with Studio !K7 and ultimately signing with the label to produce their awesome end-of-the-century Close The Door LP (along with a string of 12"s and albums to follow).[23]

This was bold, tactile music embodied in the physical world, undeniably rugged yet imbued with a strange elegance, beauty, and splendor all its own, haunted by a sense of mystery and longing just at the edge of perception. These offbeat '90s breakbeat records seemed to close a circuit stretching back to not only Spoonin' Rap’s hip hop in chrysalis, but also weird '80s electropop like Silicon Soul’s “Who Needs Sleep Tonight”, the sprawling overcast techno soul of BFC’s “Please Stand By”, and even the proto-trip hop post punk of Colourbox’s “Baby I Love You So” b/w “Looks Like We're Shy One Horse/Shoot Out”.

The latter was an undeniable highlight of Andrew Weatherall’s Nine O'Clock Drop compilation, released a few years later, which did a brilliant job of capturing this particular “lattice of coincidence” right there at the turn of the century. The next logical step back to the future, it hinted at the thematic connections between the two eras, just as Bristol luminaries like Smith & Mighty and Tricky provided direct links back to Mark Stewart,[24] or how FSOL wired 400 Blows, Fats Comet, and 23 Skidoo right up to the present day with their BBC Radio 1 Essential Mix 2 (6/3/95). In retrospect, the trilogy of Terranova’s DJ-Kicks, Nine O'Clock Drop, and FSOL’s mix make as strong a contender as any for planting the initial seed in my mind for the whole “Terminal Vibration” concept that I've been toying with for the last half-decade or so, which initially asked the question “where does post punk intersect with machine funk?”[25]

The core thesis boiled down to the idea that the 1980s post-disco nexus — as exemplified by the wild collision of sounds unfurled on New York’s turn-of-the-decade dancefloors[26] — provided the crucible for '70s-era innovations like post punk, dub, hip hop, funk, disco, synthpop, Fourth World jazz, and even prog and metal (to a degree) to mix and mingle in a massive soundclash that threw up a whole brace of mutations and innovations ranging from electro, freestyle, house and techno to alternative, post rock, beatbox and industrial, and later even swingbeat, rnb, dirty south, grime, dubstep and “on and on and on and on like hot butter on — say what — the popcorn.”

If there's one record that embodies this whole phenomenon, its My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts (along with its twin brother, Remain In Light). With dense, multitimbral Fourth World grooves and proto-sampladelia in full effect, its as if the next four or five decades of music were laid out in advance like cards on the table. Tunes like “Regiment” and “The Jezebel Spirit” hit you with the sort of off-kilter dancefloor punch that you'd swear could've only been cobbled together in the wake of the Second Summer Of Love, while “Qu'Ran” and “The Carrier” sound like something that might have seeped out of Bristol in the early-'90s, during that period when Massive Attack were remixing figures like Les Négresses Vertes and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan to brilliant effect.[27]

In fact, side two of Remain In Light treads the same path as later trip hop talismans like Maxinquaye and Protection, with its low-slung edge-of-the-dancefloor moves caught in a state of mid-dissolution into the psychedelic haze of dream logic and pure atmosphere (rhythm and vibes always a hypnotic combination). When I was young, I'd always assumed “Once In A Lifetime” was a late-eighties/early-nineties record,[28] at the time sounding to me just like turn-of-the-decade new wavers picking up the signal of swingbeat's recent rhythmic innovations (a la Teddy Riley, Guy, and Bell Biv DeVoe),[29] rather than a by-then ten-year-old track that just so happened to unearth similar terrain by way of a meeting of the minds with Brian Eno and a burgeoning obsession with West African polyrhythms. At any rate, both records exemplify the notion of trying to make future music with the tools you're stuck with in the present... and somehow managing to pull it all off.

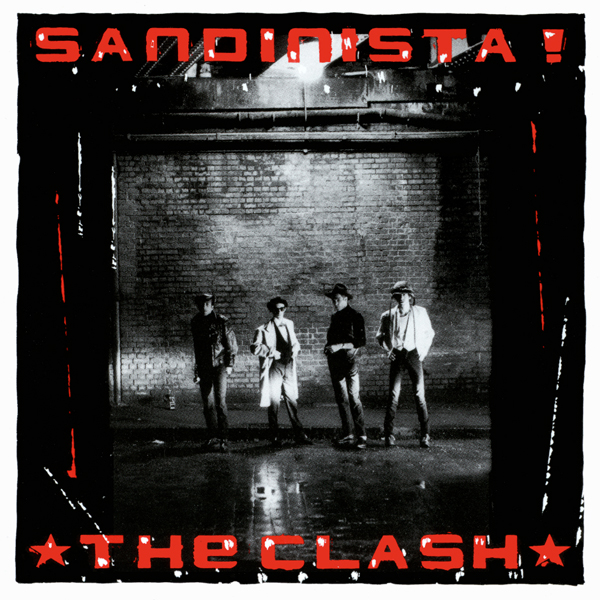

In recent years, I've grown to see The Clash’s Sandinista! in a similar light.[30] Not as legendary a record as Remain or Ghosts — in fact, it's usually either cautiously derided or dismissed out of hand altogether — I've grown to see it as one of the key records of the era, the next step down the turnpike from PIL’s Metal Box and Ian Dury’s New Boots And Panties!!. At first, the dense, swampy mix was almost too much for me to grab hold of — sonically speaking, it was evasive, mercurial, and practically slippery to the touch — but I gradually acclimated to its waterlogged production aesthetic to the point that even London Calling started to sound a bit dry by comparison.[31] It was also the most perfect realization of the band's dub and funk obsessions, imbued with the chaotic spirit of New Orleans and Kingston in equal measure. Truth be told, I can't think of another record remotely like it.[32]

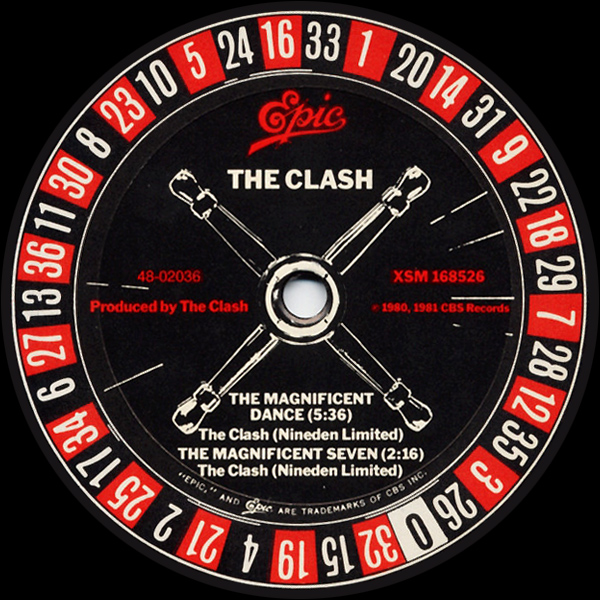

So my appreciation of Sandinista! moved through distinct phases: I went from picking out specific gems from the triple-album's marathon two-and-a-half-hour running time (“hey, the album version of “The Magnificent Seven” is phenomenal!”) to falling in love with something like half the songs included, and then slowly starting to dig more and more of the record's most offbeat cuts... and that's when things really started to get out of hand. Before I knew it, the number of tunes that I didn't like began to approach zero. The dub versions all go without saying, and most of those solarized pop songs and strange dancefloor burners were brought on board quickly enough, but then all the bizarre experiments and wispy half-songs started to feel crucial too. I've grown to love audio sketches like “Broadway” and “Junkie Slip”, and I couldn't imagine doing without the strange automat beats of “Silicone On Sapphire”, the acid-fried collage “Mensforth Hill”[33] or the ambient rework of “Police & Thieves”, “Shepherds Delight”.

Taken as a whole, I see Sandinista! not only as the ultimate crystallization of the disco punk impulse stretching back to Roxy Music’s “Pyjamarama” and The J. Geils Band’s “Back To Get Ya” (hell, maybe even further back to The Soft Parade), but also a strange precursor to the sort of dusted downbeat sound that defined large swathes of pop music in the '90s. This is borne out in the music recorded by the band's individual members after The Clash broke up. Obviously, there was Mick Jones’ Big Audio Dynamite, with their wholesale embrace of hip hop's beatbox and sampladelia methodology (and later, early rave culture), but don't forget the The Mescaleros trilogy that Joe Strummer put out at the turn of the century, records that were as dusted as Odelay or Paul's Boutique. They were also shot through with the same sort of bottom-heavy beatbox pressure that industrial-strength, dub-minded dancefloor stalwarts like Renegade Soundwave and Meat Beat Manifesto had been laying down for well over a decade.[34]

And this is more or less where I came in. Even before I'd really gotten into beats in the first place, I remember obsessing on tunes like “This Is Radio Clash” and “The Magnificent Seven”, plus Big Audio Dynamite’s “Free”, “Medicine Show”, and most especially “Contact” — ears pricking up when the breakbeat acid coda kicked in 2/3 of the way through — so with the benefit of hindsight it almost seems like my ultimate taste in music was a foregone conclusion.[35] I'd already honed in on many of these aspects of the music I started out with, so when I finally did discover beats they really just gave me more of the same, only more so... and that only made me appreciate the old records all the more. From then on, the old and the new simply fed back and forth on each other's energy, building and building in parallel over time right up to the present day. And in the intervening years, the new has become old and old became new many times over.

Looking back now, this has clearly been the lens I've been viewing it all through the whole time. As dance music kicked up routes stretching back to the same places where I'd started my whole journey — and hinted at a teeming kaleidoscopic world bubbling just beneath the surface — those early foundational sounds took on a new life of their own even as they imbued their descendants with a depth and framework that only the cascade of history's dominoes brings. “The Magnificent Seven” sounded different to me in 1996 than it must have when it first came out in 1980,[36] and it sounded different still in 2003 when the post punk revival was in full swing. And it's only continued to shift and shimmer through changing perceptions year by year, taking on new shades and carved edges right up to the present day. It's the same way with eras: just as you can hear the echo of the '70s in the dancefloors of the 1980s, so too can you find premonitions and a grand hallucination of the '90s right there in the decade of Terminal Vibration.

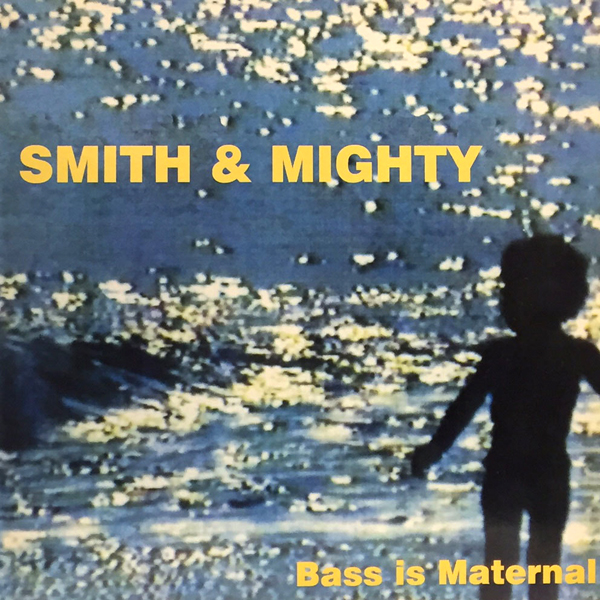

Think of the way Colourbox or Maximum Joy occasionally manage to sound like Smith & Mighty circa Bass Is Maternal with records like Baby I Love You So and Why Can't We Live Together (respectively), or how the glistening soundscapes of The Future Sound Of London’s Accelerator and other early Earthbeat sessions mirror the old Compass Point records like Wally Badarou’s Chief Inspector and Gwen Guthrie’s Padlock, or the fact that The Special AKA’s In The Studio and Tricky’s Nearly God seem to exist as twin albums separated by the gulf of a decade. Bringing it all back home, think of how Rammellzee vs. K-Rob’s Beat Bop sidestepped the next seven or eight years of rap's evolution to sound right at home in the nineties, or how Spoonie Gee’s Spoonin' Rap would mix just as perfectly into Kendrick Lamar’s “The Heart Part 5” in 2023 as it did with Reprazent’s “Watching Windows” back in 1998.

That's just the way the twisting torus of time operates, not as a long straight line but a series of concentric circles cycling in some internal orbit, a great set of shifting gears bringing some things back into view and sending others off into the horizon (for now at least). Time marches on but the Terminal Vibration remains, its waves moving through the world in and out of sync, the ghost in the machine. Who knows where it all ends up, or if it ever ends up at all?

What I do know is that Spoonin' Rap sounds better than ever as I listen to it tonight, even better than when I first heard it emerge from the cinematic grit and grime of Terranova’s DJ-Kicks or when I first popped the 12" onto the decks in a slipstream of West End and Prelude somewhere in the Heights, or at any moment in between, like when I first heard the OG version coming through crystal clear on that shiny new CD all those years ago.

So whether you'd have been talking about Schoolly D in '85 or Eazy-E in '89, Kool Keith in '97 or Kendrick in the here and now — or Cypress Hill, Outkast, and Wu-Tang in the spaces in between — Spoonie Gee’s been hanging back there in '79 all along, rhyming about how he'll “rock on rock on to the break of dawn” and “your hands can't hear what your eyes can't see”, sounding right at home in the moment and older than old school all at the same time.

And on Spoonin' Rap, he's timeless.

Footnotes |

|

|---|---|

|

I've gone on and on many times before about the dense, cinematic qualities of this mix, sounding like nothing so much as a wired Travis Bickle taking a left turn into the “A to the muthafuckin' Z” scene in Wild Style while Stalker plays on a beat up television set caught in the background through a first floor apartment window in total disregard to the scene playing out below. |

|

|

In another stroke of luck, relatively underground rap discs like Peanut Butter Wolf’s My Vinyl Weighs A Ton and the Dr. Octagon album managed to fly below the PRMC radar by virtue of being on smaller labels that didn't bother to play that game (i.e., “nobody gives a fuck about the voice actors!”). |

|

|

Truth be told, I still think “Spoonie Rap” is the better title. |

|

|

I distinctly remember hearing “Freaks Come Out At Night” on the radio A LOT at the time. Plus, it was in Jewel Of The Nile! |

|

|

Alongside my beloved Sugar Hill Band, who'd later mutate into Tackhead/Maffia/Fats Comet... but that's a whole other story. |

|

|

For example, there was Arnold Schoenberg’s Variations For Orchestra in 1928 and Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera The Nose in 1930. Even later in the century, György Ligeti’s Concerto for Piano And Orchestra debuted in 1988 with the Flexatone in tow. |

|

|

Another all-time favorite of mine, For You manages the rare feat of sounding lo-fi and crystal clear, half-lit and sun-glazed all at once. |

|

|

Call me crazy, but I've even grown to hear a bit of the subdued Beefheart (specifically things like “Her Eyes Are A Blue Million Miles” and “Where There's Woman”) in the way Spoonie’s almost pre-conscious abstraction meshes with the low-slung backdoor rhythm. |

|

|

Only just realized that I was the exact same age when I first heard it. |

|

|

Toop, David. Rap Attack #3. Serpent's Tail, 2000. 92. Print. |

|

|

This is where I could devolve into listing a bunch of tangentially relevant contemporary music that I loved at the time, so you know I can't resist:

* Plus their concurrent BBC Radio 1 Essential Mix 2 (6/3/95) Note: Not all of these are great albums, but they're all ones that I'm still rather fond of (at the very least for a handful of key tracks). At any rate, all of them have remained in my collection to this day. You'll probably already be familiar with most of them, and it is a bit of an indulgence, but it was fun to reassemble this particular set of discs in order to recreate what the era felt like to me on the ground circa 1997-1998. Taken as a whole, they provide a great thumbnail sketch of where I was coming from at the time. |

|

|

There was plenty of stuff lurking on the radio at the time (in fact, there's even some great examples peppered throughout the list above), with No Doubt’s “New” being of particular note, but by then things had really started to heat up with the whole electro revival as well, which arguably kicked off the early 21st century electroclash/post punk redux in the first place. But this is really another story in its own right... in fact, I've already broken out a couple paragraphs from this footnote for a fractal future feature somewhere down the line. |

|

|

The reason for this was twofold: Snakes and I went in 50/50 on a pair of Gemini decks and started spinning vinyl in 1999, but really there was just so much great music that you wouldn't get to hear otherwise (particularly in the realm of dance music). Plus, old records were still dirt cheap at the time (typically 25 cents a piece), so we'd grab all sorts of stuff to spin and sample. In fact, that's a whole other potential list right there... |

|

|

Interesting to note that Spoonie Gee kicked off an (admittedly one-sided) early rap feud in 1986 with “That's My Style”, where he accused Schoolly D of biting his sound! I'd argue that Too $hort might be an even stronger comparison. |

|

|

Possibly my favorite rock song of all time, the b-side to Adam And The Ants’ Zerox simply blew me away when I first heard it at the impressionable age of 14. Nothing had prepared me for its deceptively sloppy trad rock pileup delivered with turn-on-a-dime angular post punk precision, perfectly straddling the line between punk, glam, biker rock, grunge, and metal. Twenty-five years later, I still haven't heard anything remotely like it. |

|

|

You want NAMES!?! Ok, how about Camp Lo’s Uptown Saturday Night, All City’s Metropolis Gold, and Cru’s Da Dirty 30, right there in N.Y. some twenty years later? Or take it down south with Goodie Mob’s Soul Food, Devin’s The Dude, and Nelly’s Country Grammar. What about The Pharcyde’s Labcabincalifornia, Too $hort’s Get In Where You Fit In, and Tha Alkaholiks’ 21 & Over out there on the West Coast? Deeper still, check out Jay Dee’s Welcome 2 Detroit, Slum Village’s Fantastic Vol. 1, and Terrence Parker’s 3 Minute Blunts coming out of Detroit to slow burn fanfare over the next ten years. Or maybe even Aaliyah’s One In A Million, Queen Pen’s My Melody, and Mýa’s self-titled debut on the rnb tip? Trip hop? Don't make me laugh... have you ever heard of Tricky? |

|

|

“Terranova have got their kicks by gathering together a bunch of their favorite tunes, locking themselves in the studio, and enhancing the results with keyboard overlays, effects and street recordings.” (Unknown Author. Liner notes. DJ-Kicks. Terranova. Studio !K7, 1998. CD.) |

|

|

Check out the phenomenal bleep/synth solo that pushes the closing bars of 69’s “Ladies & Gentlemen” into Backroom Productions’ “The Definition Of A Track”, its sound hovering somewhere between Boards Of Canada, Dâm-Funk, and the final scene from The French Connection. |

|

|

Taking the kosmische modal jazz of the sprawling eight-minute original — defined by its placid, overcast mood and angelic guitar lines from Krautrock luminary Manuel Göttsching — Avenue A reworked the tune into a pile-driving big beat monster, complete with speaker-shredding acid and mile-high drums that could break the levy back into the ocean. One of the great unsung moments of the genre, if more big beat had sounded like this, it might have outlived the decade. “Let that shit come down,” indeed. |

|

|

According to Freddy Fresh’s exhaustive compendium The Rap Records, the Spoonie Rap 12" came out in 1987, while the label on the record itself indicates a 1980 copyright.* The Discogs entry doesn't come down one way or the other, but it shows the subsequent releases on Harlem Place all springing from a relatively short timeframe (1995-1996) in the mid-nineties.** * (Fresh, Freddy. The Rap Records. Howlin' Records, 2004. 96. Print.) ** (https://www.discogs.com/label/5859-Harlem-Place-Records) |

|

|

At the time, this was actually much more common than the straight reissues you'd start to see more often by the 21st century, since DJs wanted beefed-up versions of classic cuts that would slot right in with the latest sounds coming out every week (an approach that seeped into the culture via Jamaica’s constant churn of versions and dancehall retrofits, where everything is potential compost for the future). Things were still moving so fast at the time that it was all about plugging everything into the crackling energy of RIGHT NOW. |

|

|

Interestingly enough, in the course of putting this piece together, I discovered a Re-mix Of Spoonie Rap 12" on Heavenly Star, dating from 1982. I wonder if this is the same “Remix” found on the Harlem Place 12", which is more or less the basis for the “Atmospheric Version”, with the latter taking the mix even further into tweaked-out abstraction. Bringing to mind 12" singles like The Clash’s “This Is Radio Clash” and 400 Blows’ “Declaration Of Intent”, where each sequential version got more dubbed-out and decomposed as you progressed, their respective final mixes often being described as “unlistenable” (“I disagree Gary... I disagree.”). At this point in my life, I've got bigger fish to fry than trying to get to the bottom of this particular caper by tracking down what is now a relatively pricey record, but it's funny to think I might have chanced into being right on the money way back in high school when guessing the year this particular recording came out... |

|

|

This wasn't an altogether uncommon career path at the time, with other DJ-Kicks alumni like Smith & Mighty, Nicolette, and Kruder & Dorfmeister all signing with the label for new albums and/or having classic ones reissued. This was actually how I was able to get ahold of Nicolette’s Now Is Early and Smith & Mighty’s Bass Is Maternal — two of my absolute favorite albums ever — at such an early stage. |

|

|

Both figures worked with Stewart early in their respective careers: Smith & Mighty produced the dub for Mark Stewart + Maffia’s This Is Stranger Than Love (in fact, they'd actually produced the original instrumental as well, uncredited*), while Stewart himself produced Tricky’s debut single Aftermath and even contributed memorable wraithlike vocal lines to its protracted coda. * (Pearce, Kevin. A Cracked Jewel Case. Your Heart Out, 2016. “Stepper's Delight”. Digital.) |

|

|

The original article was published in November 2016 at the Parallax Room, in the wake of a week-long business trip to the Bay Area where I listened to Chrome and Tuxedomoon while rereading the San Francisco chapter of Rip It Up And Start Again (this spurred on by catching Chrome and Dâm-Funk at The Casbah in the months prior, on two separate nights). The trip was capped off by dinner with my uncle at a choice Indian spot in downtown Redwood City after checking out a record shop down the street from his place that happened to have something like a dozen copies of Funkadelic’s The Electric Spanking Of War Babies in stock. Later, we even hit his regular thrift spot, where I found a mint copy of Edwyn Collins’ Gorgeous George on CD for a dollar! Needless to say, we lost track of time and it all ended with a mad dash back to the airport to make it in time for my flight home. I can still remember listening to Alexander O'Neal’s debut for the duration of the flight (S.F. to San Diego the perfect length for your typical 40-45 minute album), city lights stretching out below in all directions. Now that's what I call Terminal Vibration! |

|

|

Embodied by nightclubs like the Paradise Garage, The Roxy, the Mudd Club, and the Funhouse. |

|

|

Daddy G’s much later (2004) entry in the DJ-Kicks series is well worth checking out on this front, as it includes both of those Massive Attack remixes, along with Mélaaz’s awesome “Non, Non, Non” and Massive’s own “Karmacoma (The Napoli Trip)”, both of which are cut from the same cloth. |

|

|

Once again, I remember suddenly hearing “Once In A Lifetime” on the radio all the time right around then, further warping my perception of it as a relatively new release (strangely enough, I don't recall hearing it on the radio or seeing the video on MTV any earlier than that). |

|

|

Post-new wave/new pop figures like Information Society, Nu Shooz, and blockbuster-era Scritti Politti would all more or less fit this general drift. |

|

|

As paired with the This Is Radio Clash (12" Single), a superb distillation of all its themes into a beautiful four-mix 12" package. |

|

|

I still love the album, don't get me wrong! In fact, hearing its production once compared to The Stones’ Some Girls only made me love it even more. It also casts Exile On Main St. in a whole new light as well, now sounding to me like a very London Calling sort of album.

That being said, I wouldn't rule out a preference for Sandinista! being a possible signpost for impending madness... |

|

|

Even the most plausible contenders — records like The Special AKA’s In The Studio, Ian Dury’s Lord Upminster, and The Good, The Bad & The Queen — aren't quite right, each in their own way seeming more like fellow travelers that happen to overlap in certain ways than managing to cover all the bases of Sandinista!’s sprawling six sides. |

|

|

I can never resist the urge to point out how the distinctive crashing sound that opens “Mensforth Hill”, along with Joe Strummer’s acappella vocals from “The Magnificent Dance”, both crop up in Reese’s great unsung slab of Detroit techno, “You're Mine”. Perhaps it's not surprising that a Paradise Garage veteran like Kevin Saunderson would've had the The Magnificent Seven (12" Single) lying around, but him trawling through five sides of Sandinista! back in the '80s to discover “Mensforth Hill” is some next-level bizzness... |

|

|

It's also worth mentioning that Paul Simonon was a core member of Damon Albarn’s post-Gorillaz/post-dusted crew The Good, The Bad & The Queen, rounding out the rhythm section alongside none other than Tony Allen (so Terminal Vibration it hurts!). As noted above, The Good, The Bad & The Queen is about as close as anyone's come to paralelling the Sandinista! sound at all. In fact, something like “Rebel Waltz” would fit realatively comfortably on side one of TGTBATQ’s debut. |

|

|

Another similarly early incursion was The Raw & The Remix compilation by Fine Young Cannibals, which Brian (always musically adventurous, even then) picked up around the same time. The disc featured remixes by Bristol luminaries like Nellee Hooper and Smith & Mighty, raps by Dave Angel’s sister Monie Love, and the awesome “Tired Of Getting Pushed Around (The Mayhem Rhythm Remix)” by 2 Men A Drum Machine And A Trumpet, which I listened to obsessively at the time and turned out to be remixed by none other than Detroit godfather himself, Derrick May. You couldn't make this stuff up! |

|

|

In fact, it didn't even occur to me that it was a punk take on disco rap until many years later. |

|